Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Clean Energy Transitions: Time for a New Approach?

A "price gap-plus" approach could bring carbon prices and environmental costs into the equation.

About this report

The IEA has long described fossil fuel subsidies as a ‘roadblock’ on the pathway to clean energy systems and provided data and advice to support their removal. The methodology is a “price gap approach” where we establish a market reference price and then compare it with the price paid by consumers. When the end-user price is lower than the reference price, it is counted as a subsidy.

But this approach does not reflect the environmental costs of fossil fuels such as carbon prices. To deal with this issue, this report suggests “price gap-plus approach”, which explores whether, and how, it might be possible to incorporate environmental aspects into the calculation of fossil fuel subsidies. We conducted analysis for six countries that are the negotiating parties for a new international Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS) – Norway, Iceland, New Zealand, Switzerland, Costa Rica and Fiji.

Our analysis underscores that adding a carbon price to the reference price is more likely to reveal fossil fuel consumption subsidies, even though are no agreed standards for carbon pricing. This issue becomes more sensitive during periods of high and volatile fuel prices, when governments opt to take actions to protect consumers.

The IEA has long described fossil fuel subsidies as a ‘roadblock’ on the way to a clean energy system and provided data and advice to support their removal. The methodology that we use establishes a market reference price for different fossil fuels – and for electricity produced from these fuels – and then compares that with the price paid by consumers. Where the end-user price is lower than the reference price, that is counted as a subsidy (called a fossil fuel consumption subsidy). The results of our most recent analysis show a startling rise in such subsidies in 2022.

This approach, which is call the ‘price-gap approach’, does not capture all the fossil fuel subsidies that are out there. There may be government interventions that tip the playing field in favour of fossil fuels but that do not affect end-user prices; production subsidies are a case in point. That is why the IEA works closely with the OECD – which tracks other types of subsidies – to produce a broader joint assessment.

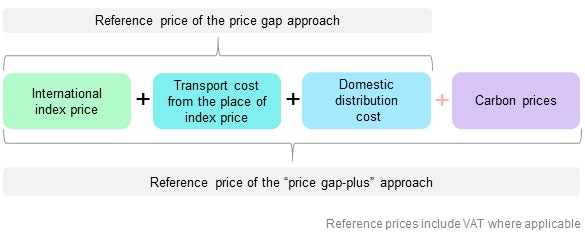

There are ways to amplify and expand the definition of fossil fuel subsidies that the IEA uses. One very important variable is the market reference price. As things stand under the IEA methodology, this refers simply to the prevailing price at which various fuels are sold on the international market, with adjustments to reflect transport and distribution costs to consumers. But this approach does not include any adjustment to reflect the environmental costs of fossil fuels such as carbon prices. This article explores whether, and how, it might be possible to incorporate environmental aspects into the calculation of fossil fuel subsidies.

The IEA has been collecting data for international fuel markets and retail prices for more than a decade. The price gap between reference fuel prices (which include international market prices, international transport costs and domestic distribution costs) and end-user fuel prices indicates how and to what extent governments are intervening in price formation. Governments are deemed to be subsidising consumers if the end-user prices are lower than the reference prices. Analysis using the IEA’s “price-gap approach” provides an annual estimate of fossil fuel consumption subsidies worldwide (see our Fossil Fuel Subsidies Database).

Our latest analysis indicates that global fossil fuel subsidies for end-users reached more than USD 1 trillion, by far the largest value that we have ever seen. This is five times higher than in 2020, a year in which countries saved on subsidy outlays due to the historically low fuel prices during the pandemic. It is often very difficult to fully quantify the level of subsidies issued for fossil fuels, as there are many avenues for the distribution of support. However, the IEA’s "price-gap approach” provides a uniform measure of subsidies to fossil fuel consumption by applying the reference and end-user prices.

Governments face conflicting priorities when it comes to energy prices. On the one hand, they are keen to avoid or mitigate the effects of price shocks and volatility, as these can have damaging effects on economies, households and business, with the worst effects often concentrated among poorer and more vulnerable communities. On the other hand, there is widespread recognition that prices should reflect not only market value but also the externalities associated with the underlying product, such as pollution and detrimental health impacts. In the case of fossil fuels, this points towards introducing carbon pricing.

Such carbon prices are already implemented in a variety of ways. About 23% of global emissions are covered by carbon price schemes explicitly. In many other cases, countries impose general levies or specific charges on the use of fossil fuels. These may not be directly linked to the carbon content of the fuels but instead encourage efficiency and fuel substitution in favour of less polluting sources of energy – and therefore push in the same direction as carbon prices.

The conceptual idea behind a revised “price gap-plus approach” is to incorporate an allowance for carbon prices in the reference price, and therefore to apply a higher and more sustainable benchmark for global end-user prices.

Price gap-plus approach

Open

This approach raises a few important practical questions about the level at which this notional carbon price should be set, and whether it should be differentiated across countries at different stages of development. There are no internationally agreed disciplines regarding appropriate levels of energy taxation or carbon prices. Moreover, carbon prices co-exist in practice with other energy taxes, so the addition to our reference price can be covered in practice by a variety of levies or charges that may or may not have an environmental purpose.

As for the level of carbon prices to apply, practice around the world offers a huge range. Some 68 carbon pricing initiatives are implemented in different countries. The price levels in these initiatives range from USD 1 to 130 per tonne of carbon dioxide (USD/t CO2), and the median value is around USD 30 t CO2. The price level depends on the purpose of the tax and trading system, reflecting the country or region’s economic conditions and policy priorities. It is extremely difficult to define the “proper” level of a carbon price. The debate over the social cost of carbon is illustrative of this difficulty, although many countries sidestep this issue by focusing instead on a carbon price that is consistent with their emissions reduction goals.

We conducted analysis for six countries that are the negotiating parties for a new international Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS) – Norway, Iceland, New Zealand, Switzerland, Costa Rica and Fiji. We took two approaches to the level of carbon price examined. The first distinguishing between different economic profiles, and the second imposing a uniform high level. For the first, we followed the tiered pricing in a recent International Monetary Fund study, which assumed a carbon price of USD 75 t CO2 for advanced economies, USD 50 t CO2 for high-income emerging economies (China, etc.) and USD 25 t CO2 for low-income emerging economies. So in our first case, a carbon price of USD 75 t CO2 is assumed for Norway, Iceland, New Zealand and Switzerland. For Costa Rica and Fiji, it is assumed to be USD 50 t CO2. In our second case, a carbon price of USD 100 t CO2 is uniformly applied to all six countries.

The key indicator for this analysis is whether the price gap is positive or negative. Positive values indicate that end-user prices are higher than the reference values, meaning that no consumption subsidy is in place. We looked at two fuels, gasoline and diesel, and applied two approaches to carbon pricing to each of them.

Difference between reference and end-user prices for gasoline by selected countries, 2017-2021

OpenIn case 1, using a differentiated carbon price, the gaps are all positive values. End-user prices cover the additional costs equivalent to the USD 75 t CO2 carbon price in Norway, Iceland, New Zealand and Switzerland, and USD 50 t CO2 in Costa Rica and Fiji. Iceland has the largest price gap, varying from USD 1.3 to 1.6 litre depending on the year. The smallest gaps are observed in Fiji, where they range from USD 0.2 to 0.4 litre. The countries with larger price gaps, Norway, Iceland, New Zealand and Switzerland, comfortably cover the additional costs equivalent to USD 75 t CO2. Fiji and Costa Rica have smaller price gaps, highlighting that the addition of a carbon price brings the reference price very close to the actual end-user prices. If end-user prices are regulated, this suggests that any additional fuel price spike – as seen in 2022 – could easily tip this calculation over into an indication of a subsidy. It also underlines the close linkages between the focus of this analysis and the affordability of energy, especially in developing economies where governments are watchful of the implications of high prices for vulnerable categories of consumer.

In case 2, the uniform high price means that the price gap shrinks considerably but is still positive in all cases. For Norway, Iceland, New Zealand and Switzerland, the gaps are much larger than the maximum yearly change in individual values over the past five years. For Costa Rica and Fiji, the gaps are close to or even less than the maximum yearly change. This implies that, in a case where the international oil price surges but domestic end-user prices do not change accordingly, it becomes more challenging for countries to cover the additional costs equivalent to USD 100 t CO2 of carbon prices.

Difference between reference and end-user prices for diesel by selected countries, 2017-2021

OpenThe results indicate that the gasoline price gaps in the six selected countries are all positive values (meaning that the end-user price covers the additional costs equivalent to carbon prices) even in the case of a uniform carbon tax of USD 100 t CO2. These findings hold up well during periods when international market conditions are relatively stable but will be tested during times of turbulence and price volatility, especially in emerging and developing economies. If the international oil price rises but regulated domestic end-user prices do not change accordingly, it will be challenging in some cases for end-users to cover the additional costs implied by adding carbon prices to the reference price. This will be particularly challenging for diesel, which is cheaper and more carbon intensive. In fact, end-user diesel prices did not cover the additional costs on several occasions in our analysis, and there were more cases for diesel than for gasoline in which the gaps were close to zero.

Getting price signals right is essential for clean energy transitions, creating incentives to use polluting fuels efficiently, to switch to cleaner ones, and to invest in efficient and low-emissions technologies. Governments need to harness these market signals effectively and supplement them with regulation and standards to enable more sustainable choices. These can include ensuring that more efficient equipment is available on the market and that consumers receive help with the upfront costs of change.

Our analysis underscores that adding a carbon price to the reference price is more likely to reveal fossil fuel consumption subsidies because the benchmark, that is the reference price, becomes higher with the addition of the carbon price. At the same time, much depends in practice on where the notional carbon price is set, and there is no agreed standard on this issue. This issue is made all the more sensitive at times of high and volatile fuel prices, when many governments are taking urgent actions to protect consumers. This analysis was conducted on fuel prices in 2021. Doing the same exercise for 2022 would reveal even more strains, especially if it encompassed natural gas markets where prices have been extremely high during the global energy crisis.